This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

When I taught seventh grade language arts, one of my favorite things to teach was S.E. Hinton’s book The Outsiders. Every year, we began the unit with a discussion about the cliques that formed in students’ lives, how these groups interacted, the unwritten rules that governed their behavior, and what happened when groups clashed or people formed relationships across group lines. After we did some reflecting, writing, and talking, we were ready to start the book.

The reading went fine, more or less. Some chapters we did in class (I would read to them, then they would read silently), and others at home. Some students became as absorbed in the novel as I’d hoped they would; others, not so much. Predictably, some fell behind in the book like they did with all assigned reading.

I checked students’ progress with occasional quizzes, we did some work on plot and characters, setting and theme, and then, after a unit test over the whole book—containing mostly questions that asked students to identify characters, setting, and key plot points—we spent nearly three class periods watching Francis Ford Coppola’s movie version of the book. And I got to drool over Matt Dillon in the movie’s opening scene again and again and again. From start to finish, the whole unit took about three weeks.

In retrospect, I’m not sure why it was my favorite. Seriously. I mean, even though I loved the book, my students’ response to it was mostly lukewarm. Maybe it was just the idea of teaching it that I loved. Maybe it was the connections I was able to make to the stuff students dealt with on a day-to-day basis. I don’t know. I taught that book a few times, and even though I looked forward to it every time, I always finished the unit a little unsatisfied.

And it’s only now, years later, that I’m starting to understand that dissatisfaction: I can’t say with any confidence that my students actually learned something from that unit. Upon deeper reflection, I’m not confident that any of my students learned anything of lasting value from at least half the lessons I taught.

This is a hard pill to swallow, because I wasn’t half bad as a teacher. I had decent relationships with my students and I believe most of them had good experiences in my classroom, but real, durable learning? I can’t say how much of that actually happened.

I don’t love admitting that.

But at least now I understand why my teaching didn’t produce a lot of actual learning: I never set clear, measurable learning targets.

Things would have been so different if I’d known about backward design.

When teachers talk to each other about the stuff they’re teaching, they often say things like this:

“What novels do you do in 8th grade?”

“Oh that’ll be perfect. I can use this when I teach the American Revolution!”

“I don’t think I can fit that in; we’re doing moon phases next month.”

We tend to talk about our teaching plans in terms of the broad topics we cover. This shorthand is practical; we’re not going to drill down into specific skill and knowledge objectives while waiting our turn at the bagel table. But when I think about the lessons I gave my students, the ones I observed in my colleagues’ classrooms, and the work I’ve seen my own children do, I think this shorthand might be a pretty fair representation of what many of us are still doing: churning out lessons that keep students busy with our content without ever getting clear about what we want them to learn.

Instead of starting with a topic, we’d do better if we start with an end goal, and that’s where backward design comes in.

For many years, teachers have been planning lessons and units of instruction like this:

Step 1: Identify a topic or chunk of content that needs to be covered.

Step 2: Plan a sequence of lessons to teach that content.

Step 3: Create an assessment to measure the learning that should have taken place in those lessons.

Notice that in this approach, the assessment is created after the lessons are planned. Sometimes it isn’t created until most of those lessons have already taken place. The assessment is kind of an afterthought, a check to see if students were paying attention to the stuff we taught them.

For most of my teaching career, this is how I planned. It’s presumably how most of my colleagues planned. I believe it’s still how many teachers plan.

So what’s wrong with it? Well, when we plan this way, we’re more likely to include content and activities that have questionable value. When teaching the American Revolution, for example, if our goal is just to “teach about the American Revolution,” we can throw in anything that has any relation to that topic: a coloring page of the Boston Tea Party, a colonial flag craft project, or a worksheet where students unscramble words like minuteman, independence, and Hancock.

This random approach creates two problems.

The first and most important problem is a lack of durable, transferable learning. One reason so many of us don’t remember much of what we learned in school is that we learned it through this haphazard, topic-driven approach. These random activities are taking up precious time that could be spent on much more valuable stuff.

The other is poor student engagement. Our students know when they’re being asked to do something pointless. If they don’t see the relevance of what they’re learning or a direct line between the content of your course and a desirable outcome, they’ll tune it out. Sure, many students will do what you ask anyway, because they want good grades and the benefits that come from them. But they’re not learning. If you don’t believe me, ask them.

In their book Understanding by Design, which was originally published in 1998, Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe introduced us to backward design, an approach to instructional planning that starts with the end goal, then works backward from there. The “full” version of Wiggins and McTighe’s original approach is pretty complex and can be time-consuming to implement. If you’re ready for that, I recommend digging into their book. For now, though, I’m just going to share the most basic version of backward design.

Here are the steps:

Step 1: Identify what students should know and be able to do by the end of the learning cycle.

Step 2: Create an assessment to measure that learning.

Step 3: Plan a sequence of lessons that will prepare students to successfully complete the assessment.

The difference in order is significant: Plan the assessment first, then plan only lessons that will contribute to student success on that assessment.

I was first introduced to this concept in my sixth year of teaching, and the genius of it completely blew me away. I used it when planning my next unit and experienced the biggest spike in student success I’d ever seen. On top of that, I was actually excited about teaching the lessons I had planned. For the first time, it felt like none of my class was wasted; everything actually mattered. There was something a lot more satisfying about doing things this way.

Let’s take a look at an example to illustrate the difference between a unit planned the traditional, topic-driven way, and the same unit planned with backward design.

At some point in their school careers, students study the phases of the moon. One pretty typical way to teach this is as follows:

In many classrooms, teachers also have students track the appearance of the moon over the course of a month, so that might be added as well.

Following this plan, a teacher would feel pretty satisfied that they “covered” the topic of moon phases. But if we look at the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), the standard relating to moon phases says that grade 6-8 students will:

“Develop and use a model of the Earth-sun-moon system to describe the cyclic patterns of lunar phases, eclipses of the sun and moon, and seasons” (MS-ESS1-1).

Note the language here: Students are meant to develop a model, then use it to describe these patterns. But in the plan above, students merely copied a model, and they didn’t use it to describe anything; even if the model required some written captioning to explain what was going on, because the model was a copy, it can’t be safely said that students were really the ones describing the system.

Then there’s the test. If we assume that a large portion of a student’s grade is based on the test, then students are not being measured on their achievement of that standard. The standard does not require students to memorize the phases of the moon. Nor does it ask them to “demonstrate knowledge” of how the whole system works. The standard wants students to develop a model and use it to describe the system.

It would be easy to blow off this distinction, to say Bah, same difference. The test asks students a lot of questions that would show an understanding of these concepts, so we’re covered.

But not really. Asking a person to develop a model is a much higher-order task than asking them to copy a model. Describing systems and patterns is way more challenging than selecting the correct description.

Developing models and explaining things is the work of real scientists: They notice phenomena, study it, then figure out how to represent those phenomena in order to make it clear to other people. To say, “Look at this! It’s interesting and it explains why things are the way they are!”

And that’s exactly what the NGSS authors had in mind: “Any education that focuses predominantly on the detailed products of scientific labor—the facts of science—without developing an understanding of how those facts were established or that ignores the many important applications of science in the world misrepresents science and marginalizes the importance of engineering.” (National Research Council, 2012, p. 43).

In other words, a superior education will teach students to think and practice like scientists. If we don’t plan learning experiences that make that possible, we’re giving them a sub-par education.

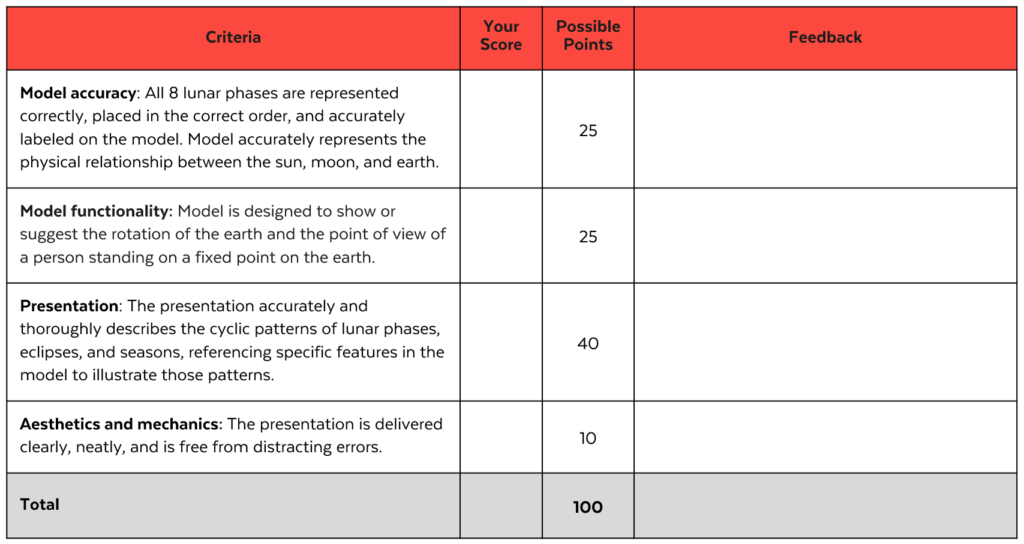

So if we re-do this unit plan with backward design, we’ll need to start by developing an assessment that would measure success with that standard. That means the assessment would not be a test where students merely label the moon phases, but a student-developed model of the moon phases along with some kind of presentation where students use that model to explain lunar phases, eclipses, and seasons.

When designing this final assessment, it’s essential that the teacher crafts a rubric that clearly outlines specific, high standards for both the model and presentation. The rubric should list criteria for the accuracy and functionality of the model, plus the quality of the presentation itself. Here’s an example of what that might look like:

With a good rubric in place, we then work backwards to determine what lessons students need to do excellent work on the final assessment.

With this “after” version, every lesson is designed to prepare students to give excellent presentations at the end. The whole time, they are using the lunar cycle vocabulary, correcting each other’s misconceptions, and just like scientists, thinking about how to explain concepts to other people.

Okay, so we’ve looked very closely at one small unit for a middle school science class. Now, take this same process and apply it to the things you teach.

Like I did, you probably also have some favorite lessons and activities. Some of these might turn out to be not just fun to teach, but also solid in terms of equipping students with knowledge and skills that will last.

If it turns out that those favorite lessons don’t really align with any standards, you might be able to revise them so they do. Or you might keep them for other reasons—not every minute of class time has to be spent on standards-based instruction. Some activities have value because they help us get to know each other better, they help students develop social-emotional skills, or they simply offer a bit of fun. But if a lesson doesn’t do any of these things, if it’s disguised as learning but is doing little more than keeping students busy, it’s time for it to go.

Using a process like backward design helps us get better at making these decisions. By making this approach part of our regular practice, we’ll be able to look back on a day, a week, or a year of teaching and say with a lot more certainty that when they were under our care, our students learned.

Reference:

National Research Council (2012). A framework for K-12 science education: Practices, crosscutting concepts, and core ideas. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13165.

Come back for more.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Incredible and something much needed for my teachers that is easy to understand and share! Love your work, podcast, all of it! Thank you!!

L Mathison says:Totally agree, I came to the comments to say exactly that same thing! An addendum or follow-up post, imagining what the new assessment for The Outsiders would be and a specific sequence of activities to build up to it, would be super!

I agree. I was disappointed not to see a revision of the Hinton lesson here. very helpful i had learnt a lot. this opened my mind and i chaned my teaching Ayada Ingram says: I absolutely agree, It was very informative and I will use this daily in my classroom Hellen Harvey says:Thank you for this and I’d the wonderful teaching resources you share – this is particularly timely for my school’s PD. I was just wondering how you would have applied BD to how you taught the Outsiders. How you taught it was an example many English teachers would identify with. Thanks again.

I love this post as well, thank you! I have the same question as Helen, how would you have applied this to your “Outsiders” unit? Your lessons sound much like many of our novel units, I’m wondering how in a lesson like this you would have flipped it BD?

Hi Kim, One of the things I always tried to remember is that I wasn’t “teaching the book.” I was teaching the reader. The book just happened to be the tool of choice. So, let’s say that in the end, I wanted kids to understand how writers use foreshadowing to drop hints, create suspense, develop a storyline, etc. That would be my end goal, objective, standard, or whatever you want to call it. Then I’d work backwards, deciding on a book that would best help me teach that literary device really well. (My book of choice happened to be The Wonderful Wizard of Oz). Then I could create lessons that would best help kids understand the impact this literary device has on the reader’s experience. I don’t remember The Outsiders, so unfortunately, I can’t help you there, but basically, you just want to start with an objective – what is it by the end of the book you want kids to be able to understand or do? This should be something they can transfer to any book they read. Then you can decide on the kinds of lessons that will lead to understanding. Hope this helps.

Thanks for the response, I am not looking specifically for how to work it for The Outsiders, more just for how to properly do this for any novel work at a high school level!

I love UBD! It helps kids make connections and just makes sense to plan that way. Done correctly, it’s a much more thorough way to teach.

We are transitioning to more online teaching because of COVID. Moving a course to 100% online creates an opportunity to reinvent existing courses. Before I created a single lesson, I loaded all my learning outcomes into the assessment backend of the software to facilitate BD. This really has helped me make the teaching materials more focused and your article has validated I’m on the right track. Thank you.

Dganit Eldar says: Joanna M says:Hi, Jennifer. I sm enjoying your articles so much ever since I discovered you while searching the Internet while researching for some writing I’m doing about problems in education. Your letter to administrators especially resonated with me, and I was so gratified to hear you express so clearly and compassionately several issues that have bothered me for years.

This article about backwards design is great too, but I have some concerns. Like so many superior teaching methods it requires extra time to revamp existing lessons and huge investments of time to listen to recorded projects instead of using class time to do so. Frankly teacher time has become such an enormous problem at my school that I found myself doing anything possible to reduce after-hours work, even at the expense of student engagement. Do you have any insights about that? Thanks for what you’re doing!

Hi Joanna! The first thing we want to address teacher time! That’s what I got hung up on when reading your question. Everything builds up and you learn something has to be sacrificed, and if you can help it, student engagement doesn’t need to be that “thing.” I so get it. And doing a culminating project that results in student recordings is only one idea. It certainly doesn’t have to look like that. YOU know YOUR students best, and you also know how much teacher time you have to put into things like this. Secondly, we don’t think you have to go back to every single lesson and redesign them with backward design and be ready to go in August. Maybe choose a single unit that may not align as well as you’d like it to and work with that one alone. And then as you teach other lessons, maybe just make notes for next year and start small! I hope this helps!

Heather B. says:Thank you so much for this post. I struggle with what my end goal should be when planning based on a topic and I think that this way of thinking will make my life a heck of a lot easier go forward. I plan on trying it out with my juniors next year!

Dganit Eldar says:Thank you for this important post. I wonder though, if the “After” example here, with the Lunar Cycle, is indeed an example of a backward design that assessing the students’ ability to develop their own model. It is nice that the rubric for the final model is created first, but the students here still copied a model that the teacher presented them with by a lecture or a video. I believe developing ‘their own model’ does not mean the freedom to choose styrofoam balls or crayons, it means STUDENTS should come up with the operative definition of what are, how many phases the moon has during the cycle, from THEIR OWN OBSERVATIONS, not from the Quizlet given by the teacher. This is still an “old school” design and memorization even if we didn’t use the Quizlet score in the final grade. The model the students suppose to be graded on is the actual conclusion from their observations that the moon has a cycle and phases and how each phase looks like. So one way to support students in DEVELOPING (vs. creating an artistic representation of a model that was already presented to them by a lecture or a video) their own model will start with the teacher asking the students to chart the moon phases each night for about a month. Teacher should NOT present a rubric that already states that the lunar cycle has 8 phases. Well, that’s the scientific model itself that we want the students to come up with. Students should come up or close to the 8 phases model ON THEIR OWN after comparing all of their observations. Then they can go on to chose a way to present it and match descriptions accepted by the scientific community to their own observations.

Another useful, well-organized and well-presented episode, Jennifer! Have you tried applying Backwards Design to your own goals for teaching? You set out to improve some aspects of the book reading lesson, and used the moon phases lesson as an example of how to make sure the students are engaged and that they actually learn something. I suggest to make all your teaching goals very explicit and do Backwards Design to yourself, regarding how you work. For example, you might say your teaching goals are:

Goal 1. Make sure students learn something useful.

Goal 2. Make it something they will remember for a long time.

Goal 3. Make sure students are engaged and see the relevance of the lesson.

Goal 4. Reduce the amount of “busy work” or class time wasted with activities that don’t teach much to the students.

Goal X. (There would be more in this list.) Now design “tests” to see if you succeeded in these goals:

Test for Goal 1: Have the students write an essay (or give a presentation) on how they _used_ the knowledge of the lesson, or think they will use it in the future.

Test for Goal 2: Survey former students to see what they have remembered about lessons you taught and (back to (1), have they used that information to do something.

Test for Goal 3: Devise metrics of engagement, such as how many times a student did something beyond the minimum expected of the lesson, or how often they came to you with a question or idea about it.

Test for Goal 4: Set up a way for students to anonymously submit a comment to you whenever they feel like they have wasted their time in class, or feel like they don’t know why they are doing the lesson. Tally these up for each student and grade _yourself_ on how well you accomplished your teaching goals. Adjust your Backwards Design of the lessons accordingly. Now for another comment (should I have posted it separately?)

I am a scientist, and I disagree that your BD moon phases example promotes doing what scientists actually do. I would say that you have crafted a useful lesson that will prepare students to be good encyclopedia writers or curators at a planetarium or natural history museum. To be good scientists, however, they should be trying to solve a mystery or help design something useful based on research results. For example, students could come up with their own motivation for why knowing moon phases is important to them, such as “How do moon phases influence the tides and therefore, how much plastic is washed up on the beach?” I think the students could be asked to design a model that will be used not just to demonstrate ideas, but to help answer questions that are presently unknown. That is what we scientists do with our models. Knowing the phases of the moon may not be of any obvious use to some students, so some scaffolding about how it ties into the real world is important. For example, for me this knowledge has been important in planning stargazing (prefer no moon) or night hikes (prefer full moon). Other fields could be brought in, such as reading literature that mentions the phases of the moon and thinking about why. Or how nocturnal animals hunt or avoid predation. In my experience, students are MUCH more motivated and engaged when they can easily see the relevance of a lesson to things they care about in the real world.

Wow Steve, I think you filled in the gap I sensed was missing: real-world application as to WHY its important to learn the moon phases. Thanks for your input.